Is there an "epidemic" of over-diagnosed mental health issues in the UK?

I’ve long been interested in psychology. In fact, when filling out my UCAS application all those years ago, my top degree choices were Modern Chinese Studies—for the few universities offering it at the time, and Psychology, for those that didn’t. What linked the two, I suppose, was a shared curiosity: my interest in people and how language shapes our understanding of the world and our place within it.

I was lucky to have two incredible teachers during my A Levels. Mr. Murphy taught English Language, and Mr. Wayman, a vivacious, 24-year-old Oxbridge graduate, taught English Literature. As passionate and magical as Mr. Wayman made literature seem, it was Mr. Murphy’s lessons on the history of the English language, his introduction to socio-linguistics and the philosophy of language, that truly stuck with me.

That introduction led me to Chomsky, and from Chomsky to Edward Said and his seminal work Orientalism. Outside of my GCSE in Japanese, Said’s work deeply influenced my growing fascination with East Asia, especially China. I was captivated by the idea of the “Other,” and how tribalism, as suggested in Said’s analysis, still shapes us today. One of the key reasons I established bilingual schools at Hatching Dragons was to explore whether learning language could help us overcome such ingrained bias and bigotry.

At the heart of all of this, I suppose I’ve been seeking answers to enduring human questions:

- What makes us fear the “Other”?

- Why are we so desperate to be right, and so ashamed of being wrong?

- Why do we crave being seen and heard?

- What makes us deny what is true, or feel deeply happy or profoundly sad?

- And what compels us to fight, day in and day out, to keep going?

Key Insights for Busy Parents

- Mental health diagnoses are rising sharply in the UK, with antidepressant use, autism, and PIP claims all significantly increasing.

- Experts are divided, some view this as greater emotional awareness, others as over-medicalisation of normal human emotion.

- Broader diagnostic criteria in systems like DSM-5 have widened the scope for mental health labels.

- Economic impact is substantial, with £13bn in lost tax revenue and benefit spending projected to reach £63bn by 2028–29.

- Younger generations are most affected, with a unique UK trend of growing emotional distress and economic inactivity.

- The blog raises a moral and societal question: how do we balance emotional validation with resilience and collective responsibility?

Before we get started with our article, if you want to read a detailed and more insightful version, click below and get it on my Substack;

Life's a Balancing Act by Cenn

Is there an "epidemic" of Over-diagnosed Mental Health Issues in the UK

Read on SubstackExplosion in Mental Health Problems

These reflections came to mind in light of recent media coverage around Health Secretary Wes Streeting’s remarks on the “over-diagnosis” of mental health issues. Here he is discussing the issue on the Laura Kuenssberg Breakfast Show.

It seems to align with the Government’s broader strategy of reducing the welfare bill and pushing people back into work. But leaving aside binary arguments over whether claimants are “benefits cheats” or genuinely in need, it's important to recognise that this debate is not new.

Consider this Intelligence² debate from 2014:

“Psychiatrists and the pharma industry are to blame for the current ‘epidemic’ of mental disorders.”

Much of what was discussed then remains true today. The debate revolved around philosophical questions about what it means to be human, and whether facing and overcoming emotional struggles is part of that very humanity.

As Will Self argued:

“It’s not the chemical imbalance in the brain that should concern us, but the moral imbalance in the society that expects happiness to be perpetual, and sadness to be a pathology.”

Have we become incapable of handling hardship? Do we spend too much time scrolling through the perfectly curated lives of influencers, constantly comparing our own realities to their seemingly effortless abundance?

Or, conversely, have we rightly moved toward a medicalisation of emotion, treating pain and grief as conditions that can and should be treated? The rising number of diagnoses and prescriptions might suggest, as argued by Dr Simon Wesseley (in that same debate), Dr Lucy Foulkes, and Dr Stephen Hinshaw, that this growth is actually a sign of a culture becoming more emotionally aware, not necessarily “more ill.”

As Dr Foulkes puts it:

“Increased reporting doesn't necessarily mean more illness, it might mean more honesty.”

Perhaps previous generations simply suffered in silence, while we are now entering an age of emotional awakening, where both positive and negative experiences are valid and deserve to be acknowledged. But does such openness help us heal, or does it suppress our resilience?

Want to see how we create a nurturing environment that supports emotional wellbeing and resilience in children every day?

Book Online TourBook A VisitGrowth of Diagnostic Categories

Growth of Diagnostic Categories

One concrete fact: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has evolved significantly. From 106 disorders in its first edition in 1952, it peaked at 297 in 1994, and now sits at 157 in the 2022 fifth edition.

On the surface, that looks like progress. However, while the number of distinct categories has decreased, the scope within those categories has widened, allowing more people to fall under broader diagnostic umbrellas. ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Generalised Anxiety Disorder are key examples.

Take Autism Spectrum Disorder: it now includes previously separate diagnoses such as Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Syndrome, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, and PDD-NOS. As the parameters broaden, more people are (in)correctly diagnosed depending on the clinician’s judgment. In fact, autism diagnoses in the UK rose by a staggering 787% between 1998 and 2018.

Let’s now look at some sobering statistics:

- In 2023, the NHS reported that 8.7 million people were prescribed antidepressants, around 15% of the population.

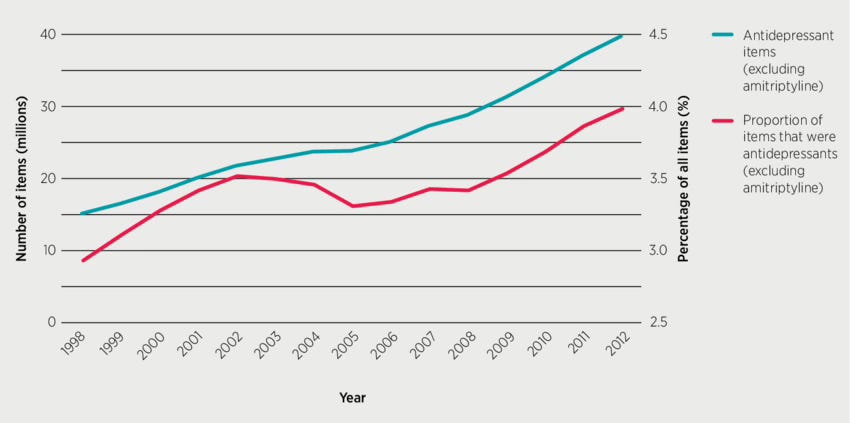

- This ResearchGate report from 2014 shows the upward trend between 1998 and 2012, clear and stark.

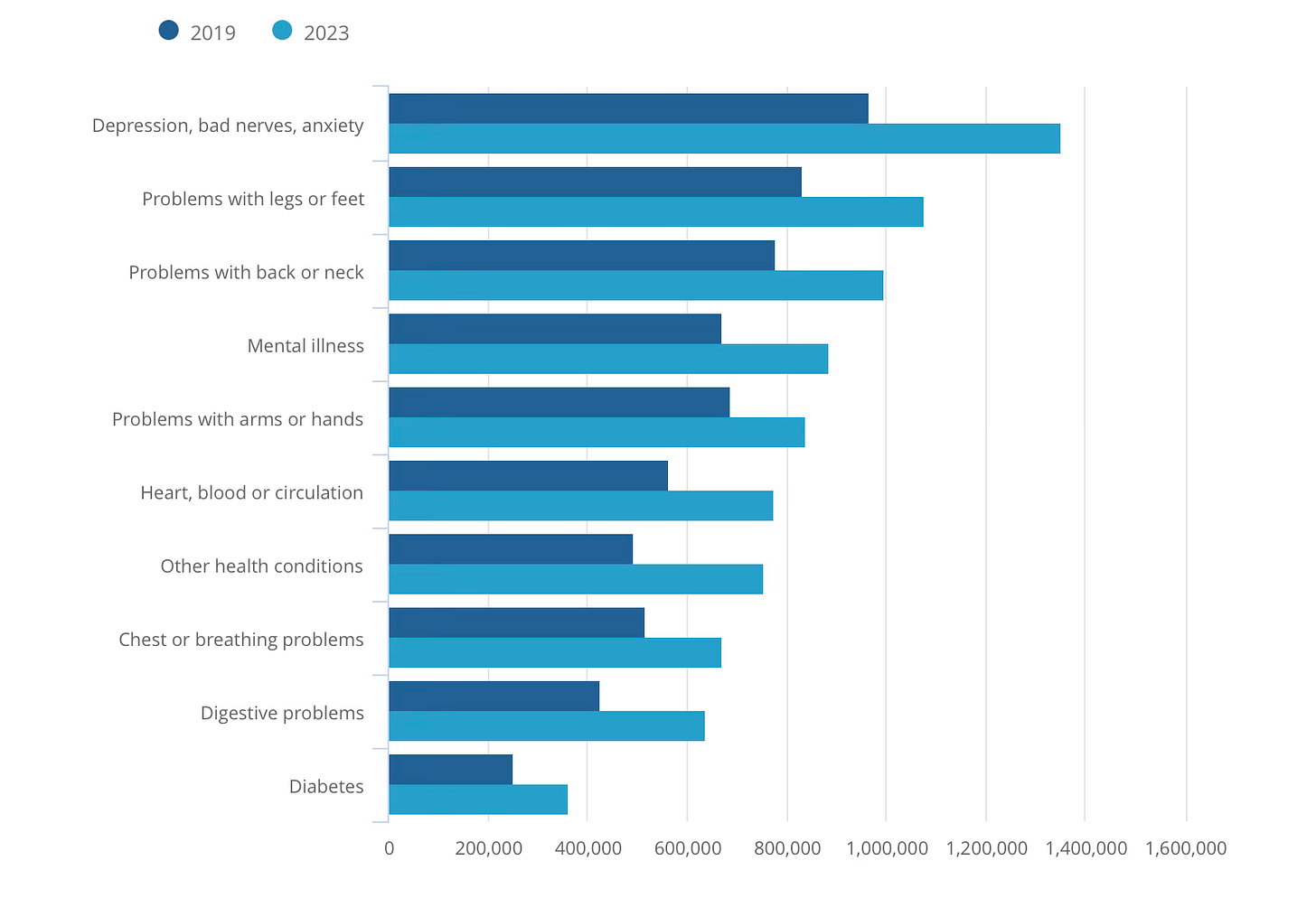

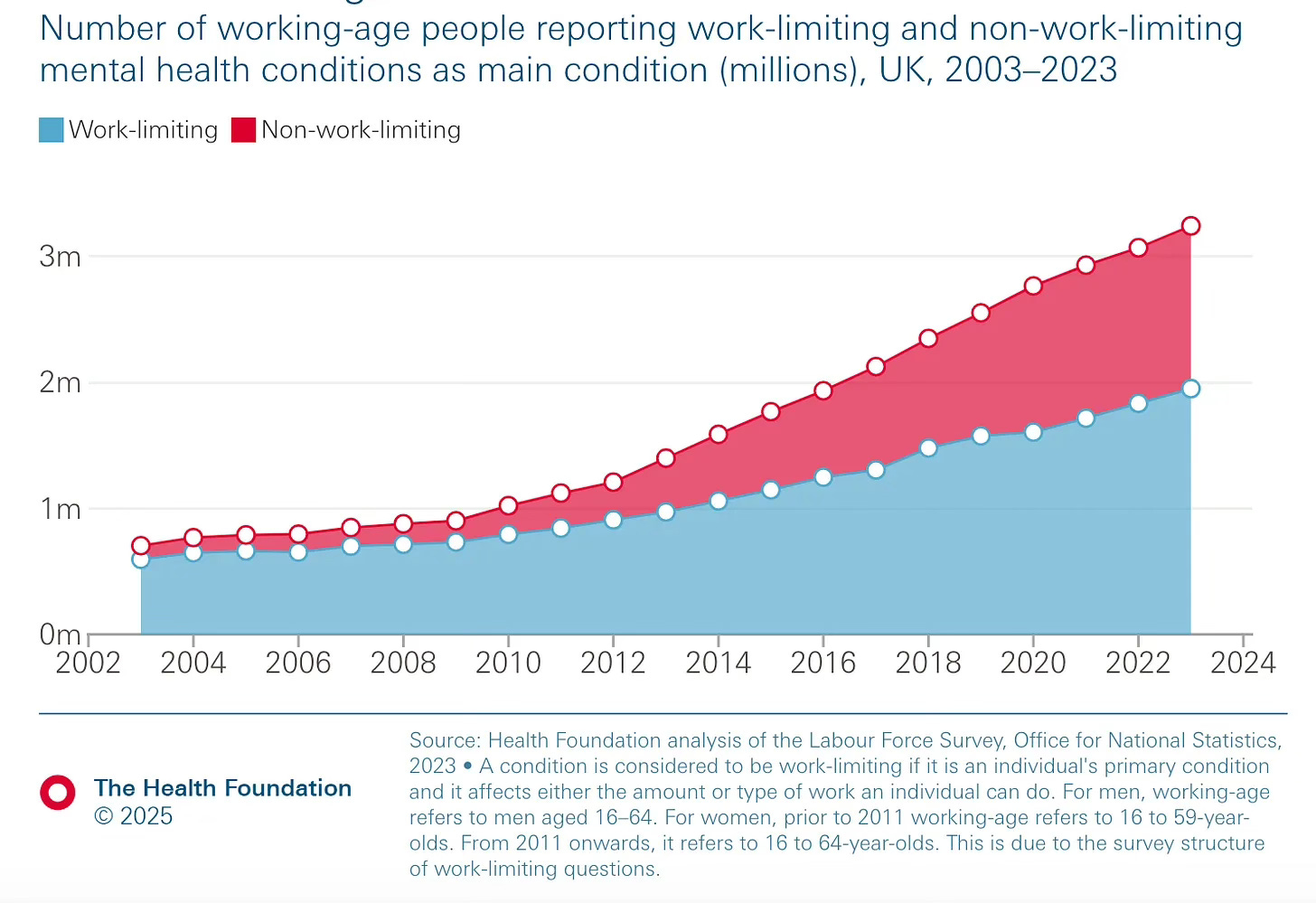

- The number of people economically inactive due to long-term sickness now exceeds 2.5 million (an increase of over 400,000 since the start of the pandemic), according to the ONS. Of these, more than 1.35 million (53%) cite depression, anxiety, or similar conditions, a 40% increase since 2019.

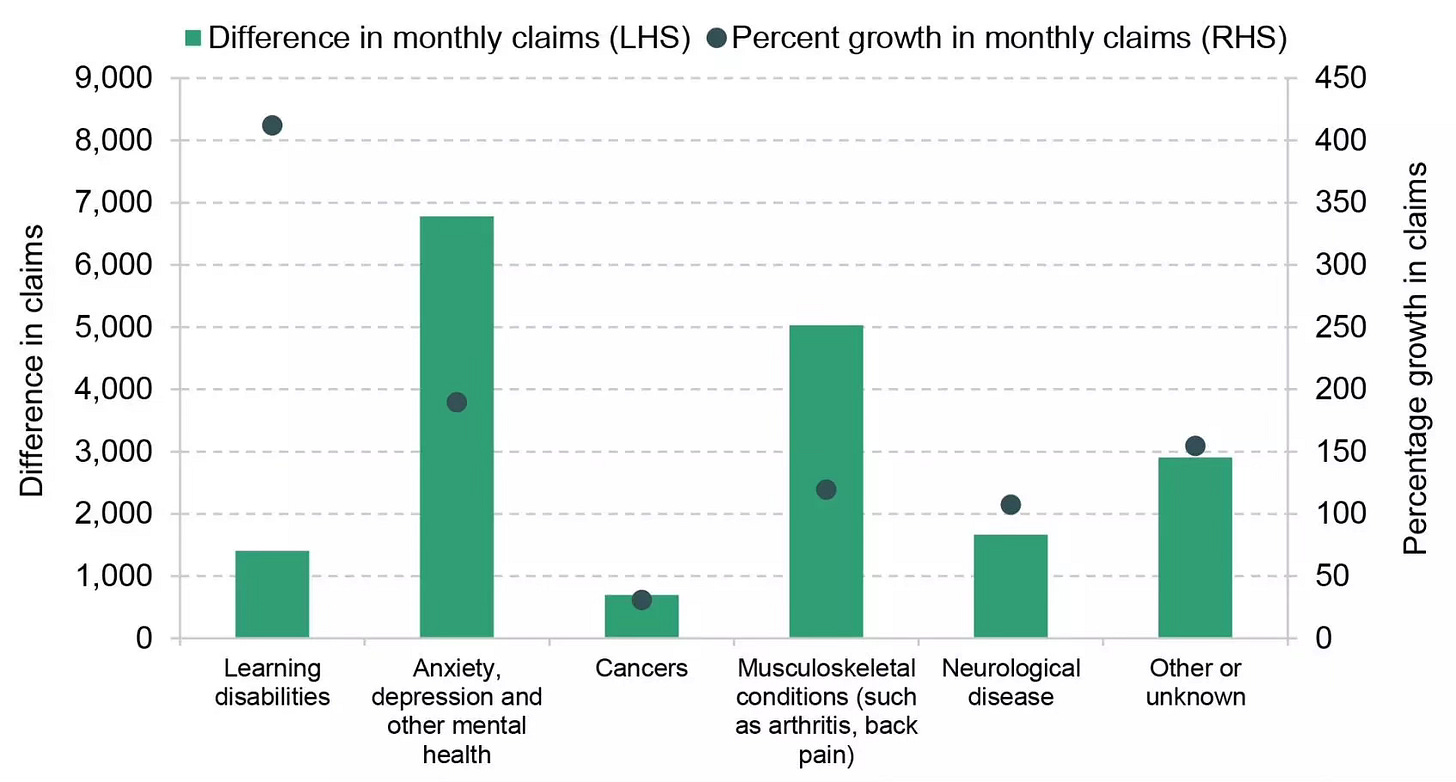

- The Institute of Fiscal Studies reported a nearly 200% rise in Personal Independence Payment (PIP) claims for anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues between 2019 and 2024.

Despite the expansion in diagnoses and increased availability of both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments, the overall trend is clear: more people are seeking help, and more help is being delivered, but we’re not getting any happier.

So, as others have asked: Where is this heading?

The Evidence is Telling

Whether rising emotional awareness is morally “good” or “bad” is difficult to untangle, at least for me. I’ve always believed (perhaps incorrectly) in the value of the collective over the individual, especially when it comes to emotional wellbeing.

I’m not a psychiatrist or psychologist, so my views come from personal values, shaped by my parents, and by the countries and cultures I’ve lived in. I’m probably deeply emotionally suppressed.

But I believe the collective good is the social good. There is meaning, I think, in individuals feeling that their contribution, however costly emotionally or otherwise, adds purpose to life. I want to believe we aren’t inherently selfish creatures (though many cognitive scientists might disagree), but rather that we find value in being part of a group, and in supporting mutual outcomes.

Case studies on the mindset of military units and families, how far individuals go to support each other because of deep emotional bonds, demonstrate what a cohesive society could achieve on a broader scale.

So, with that in mind, my question isn’t just whether emotional awareness is positive or negative, but what impact it has on society as a whole, as well as the individual.

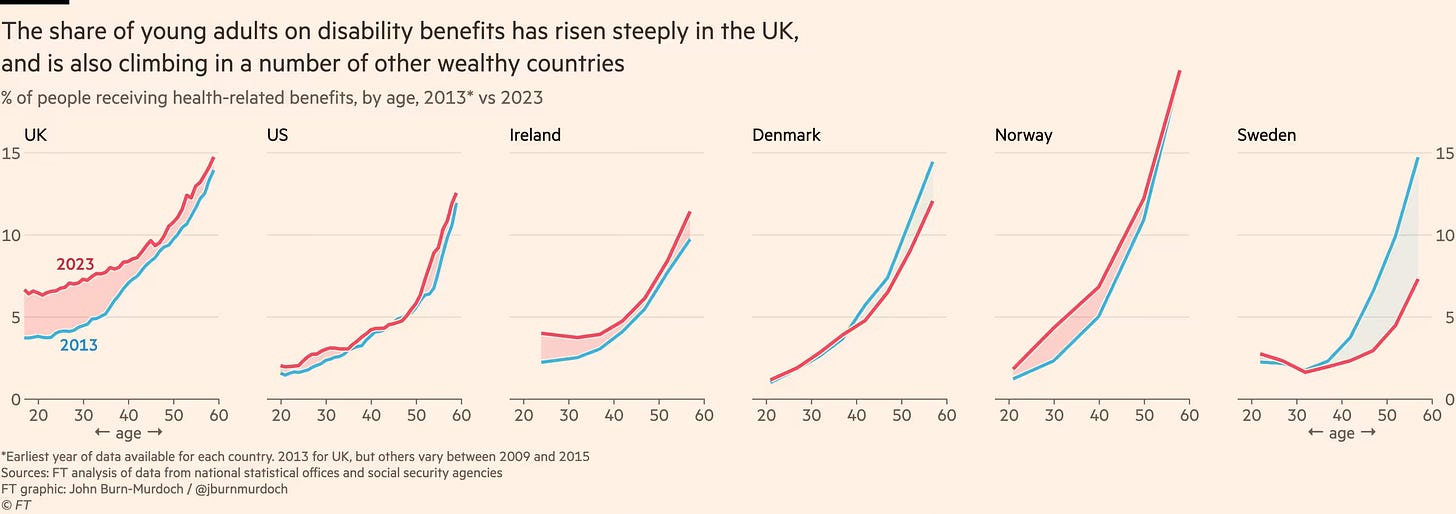

To explore that, I return to the excellent work of John Burn-Murdoch at the Financial Times, particularly his piece:

“Out of work and unwell: the worrying rise of young people on benefits”.

This forms the backbone of much of the recent reporting following Wes Streeting’s briefings, centering on the economic impact of mental health issues, and which generations are most affected.

And while emotional awareness is rising across all age groups globally, what’s unique to the UK is that the burden is felt most acutely among younger generations.

Societal Impact and Future Implications

At a time when national spending is being reviewed, and we must decide what kind of future we want for our country and our children, it’s worth examining the implications.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS):

- Health-related benefits for working-age people in the UK rose from £36 billion in 2019–20 to £48 billion in 2023–24.

- Projections suggest this figure will hit £63 billion by 2028–29, over 2.1% of UK GDP.

To put that in perspective:

That figure is comparable to our national defence budget, the same percentage of GDP we were once urged to contribute to NATO.

And the lost tax receipts from those economically inactive due to mental health issues?

An estimated £13 billion annually.*

That’s enough to fund:

- 150 hospitals

- 650 schools, or

- 420 miles of new rail track (if built as efficiently as the French, hello, HS2).

The socioeconomic cost is real.

Where Does That Leave Us?

So, where does all this leave us?

Are people gaming the system, or are they genuinely in need?

Can both be true at the same time?

One conversation comes to mind. I spoke to a young woman in the local park one afternoon. She’s a childminder for several families at the local primary school, working from 3:30 to 7:00 PM on weekdays. She told me she earned “quite well” from this. When I asked what she did during the day, she explained she drew the dole to cover her rent and spent the rest of her time enjoying drinks and daytime meetups with friends.

That exchange got me thinking, not just about her, who seemed clearly to be manipulating the system, but about the economic impact of those who choose not to work.

I stress the word “choice” here.

I’m not, and never will be, an advocate for dismantling the welfare state, I even named my son after Aneurin Bevan. Many people genuinely need and deserve support, compassion, and public funds.

But I’m not sure this young woman qualified.

And so, the moral question we each must ask when grappling with depression, anxiety, or emotional distress is this:

Do our emotional needs justify placing ourselves above the needs of society as a whole?

As Will Self put it:

“Have we become a society that cannot tolerate sadness, grief, or distress, where psychiatry has become the priesthood that offers absolution through prescription?”

I sincerely hope not.

But I fear that we’re fast developing a culture that undermines resilience, the ability to mentally and physically push through difficult times, and instead replaces it with a narrative that places individual emotional validation above all else.

It’s no surprise, then, that figures like Andrew Tate find room to operate in this space, exploiting the vulnerability of those desperate for change.

We must each find the space and time to be emotionally honest, but also retain the strength to navigate through it.

Because there is value in the struggle.

All of us face battles. All of us feel deeply. But the real question is:

Do we let the more destructive parts of our emotions define who we are, what we do, and what we’re capable of becoming?

I hope not. I hope we can use those emotions as fuel to move forward, together.

Ready to Raise a Global Citizen?

Looking for a nursery that celebrates diversity and nurtures global citizens?

Contact Hatching Dragons today to learn more about our multicultural, early years approach rooted in inclusion, empathy, and global learning.

Book a tour, register today, or reach out through our Contact page to learn more.

Related Blog Posts:

- Smartphone-Free Adulthood: Week 1 Review

- The Orchestra of the Brain: Inside Child Brain Development

- Motivation Matters: Why Parents Need Science, Not Just Instinct

- The Slow Death of Focus

References for Further Reading

- Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) – Health-related benefit claims post-pandemic: UK trends and global context

https://ifs.org.uk/articles/health-related-benefit-claims-post-pandemic-uk-trends-and-global-context - Mind – Big Mental Health Report 2024

https://www.mind.org.uk/news-campaigns/news/big-mental-health-report-2024 - UK Parliament – Student Mental Health Report 2023

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5803/cmselect/cmeduhc/174/report.html - Centre for Mental Health – Mapping Youth Mental Health

https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/mapping-youth-mental-health - Centre for Social Justice – Change the Prescription

https://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/library/change-the-prescription - Health Foundation – Mental Health Amongst Working Age People

https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/news/working-age-people-with-mental-health-problems-face-significant-barriers-to-work - ResearchGate – Trends in Antidepressant Prescriptions in the UK (1998–2012)

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260789375 - Financial Times – John Burn-Murdoch – Out of work and unwell: the worrying rise of young people on benefits

https://www.ft.com/content/42e3a9a1-f0f0-4a9d-92a7-efbfa5b8ddfd - Intelligence² Debate (2014) – Psychiatrists and the pharma industry are to blame for the current ‘epidemic’ of mental disorders

https://www.intelligencesquared.com/events/psychiatrists-are-to-blame/

Tags:

Parenting Tips, Child Development, LanguageDevelopment, EarlyChildhoodDevelopment, Neuroscientists, neurotransmitter

22-Oct-2025 22:04:38

.png?width=1200&length=1200&name=Register%20(1).png)

.png?width=1200&length=1200&name=Inquiry%20(1).png)

Write a Comment